Move semantics in 10 Minutes

Move semantics were introduced in the C++11 and provide a way to efficiently move contents of objects from one to another, instead of copying object unconditionally. This prevents unnecessary object copies, thus results in better performance and promotes simpler and expressive design.

Introduction

Consider the following scenario

std::vector<int> v1 {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7};

std::vector<int> v2 = v1;

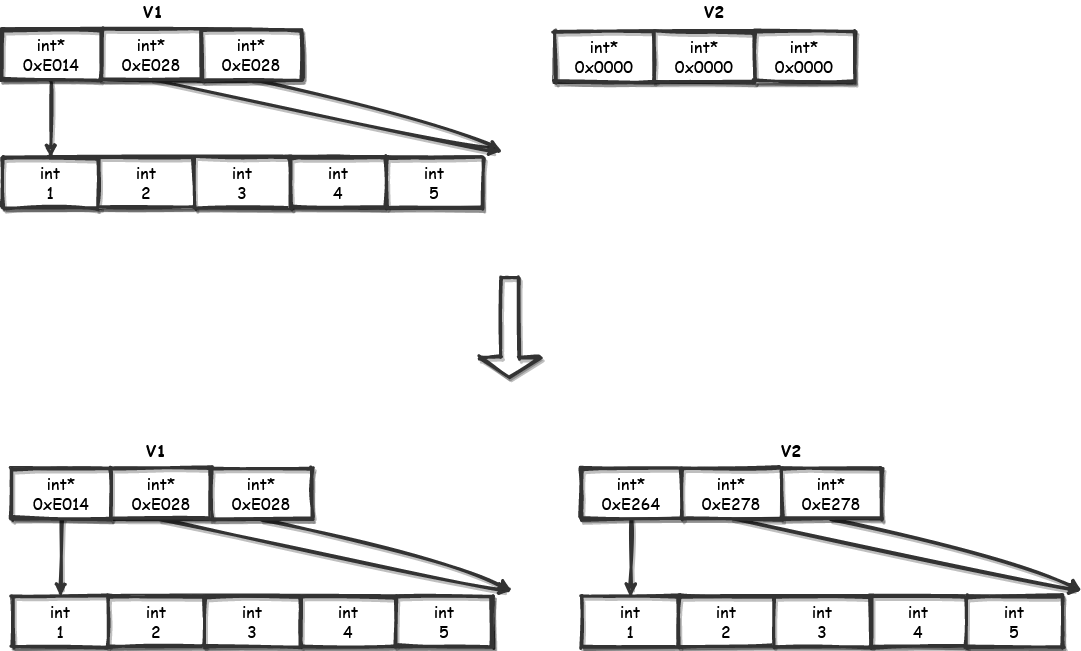

Here, v1 is copy-constructed using v2 and it does a deep copy with a possibility of extra memory allocation if v2 can not fit v1. This is expected if we want to have two independent copies of the vector without any problem due to data sharing.

Now, let’s consider the following.

std::vector<int> GetVector()

{

return std::vector<int> {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7};

}

...

...

std::vector<int> v2 = {};

v3 = GetVector();

Here, GetVector constructs and returns a temporary vector that gets similarly copied to v2 as in the scenario above.

But, do we want to create a copy here?

No!! It’d be wasteful; because the returned vector is temporary and will eventually get destroyed.

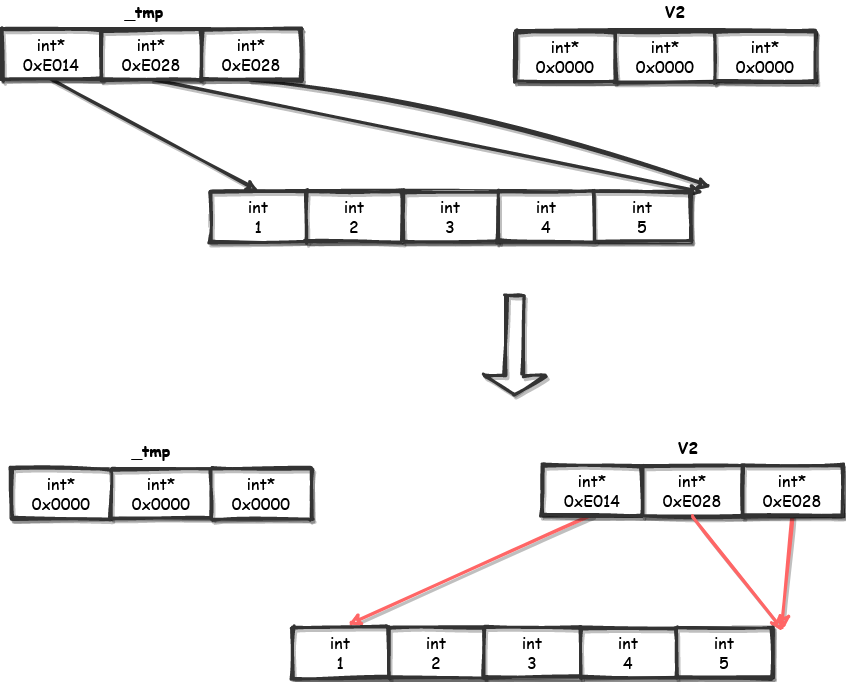

Instead, we can transfer the contents simply by redirecting the pointers of v2 to the memory locations pointed by the pointers of temp object; followed by resetting pointers in the temp object.

This effectively transfers the ownership of content from the source object(tmp) to the destination object (v2).

That’s exactly the facility move semantics provides. Move operations, in addition to being extremely cheap compared to copy, have also changed the way we design our code.

Lvalue and Rvalue

Before we deep dive into the technical details of move semantics, we need to understand the difference between an lvalue and an rvalue.

Loosely put, an lvalue is

- Anything which has a name i.e. identifier.

- Whose address can be taken.

- Assignment to it is possible.

and rvalue is

- Temporary object which exists only during the evaluation of an expression.

- Whose address can’t be taken.

- Doesn’t have a name.

//a is an lvalue as it has a name and well

// defined address.

//666 is an rvalue as it doesn't have a name

// and accessible address.

int a = 666;

// lvalue address can be taken and put into another variable.

int* p = &a;

//666 is literal constant, hence an rvalue.

// we can't do

int y;

666 = y; //error

int * z = &666 //error

//Similarly

std::string s;

//result of s+s is an rvalue

//s is an lvalue

s + s = s;

Note: lvalue and rvalue explanation above is a good rule of thumb that works most of the time. But, there are a few nuances to it in c++ standard. Eli Bendersky’s post provides a detailed introduction on this topic.

Rvalue Reference && and std::move

Before C++11, since there was no way to differentiate between an lvalue and an rvalue, because of that it always defaulted to copy operations; either using copy constructor or copy assignment operator. Even temporaries were copied, which is bad.

template<typename T, typename A= ...>

class vector

{

public:

...

//Copy Constructor

//takes lvalue

vector(const vector& rhs);

//copy assignment operator

//takes lvalue

vector& operator=(const vector& rhs);

}

// returning an rvalue

std::vector<int> GetVector()

{

return std::vector<int> {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7};

}

...

...

//lvalue

std::vector<int> v1 {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7};

//calls copy constructor.

std::vector<int> v2 = v1;

//rvalue

std::vector<int> v3 = {};

//Also calls copy constructor

// because rvalue can bind to const lvalue reference.

v3 = GetVector();

To prevent copying temporaries unconditionally, C++11 introduced a new && operator which is similar to reference(&) operator; but unlike & which binds to an lvalue, && binds to rvalues. Therefore, by using rvalue reference(&&) we can distinguish between lvalues and rvalues and formulate different strategies for copy and move operations.

How? you may ask.

Comes, move constructor, and move assignment operator functions.

template<typename T, typename A= ...>

class vector

{

public:

//Move Constructor

//takes rvalue

vector(vector&& rhs);

//move assignment operator

//takes rvalue.

vector& operator=(vector&& rhs);

}

//rvalue

std::vector<int> v3 = {};

//Will call the move assignment operator now.

v3 = GetVector();

How about moving an lvalue ?

std::vector<int> v1 {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7};

//continues calls copy constructor.

std::vector<int> v2 = v1;

std::vector<int> v3 = {};

//calls copy assignment operator

v3 = v2;

Well, C++11 also introduced std::move() which takes an lvalue and returns an rvalue reference. So to move an lvalue v1 We’d do

//calls the move assignment operator

v2 = std::move(v1);

Note:

Since, move operation causes transfer of ownership, using a moved-from object afterward i.e. v1 in the above case, can lead to trouble, because v1 will no longer own the memory it was holding onto previously. Although, being an lvalue, it has a name and lives on, until its scope expires and it gets destroyed. It can be misused in clever ways if you know what you’re doing.

If we check the definition of std::move we realize that std::move(), contrary to its name, doesn’t move anything; instead it unconditionally casts its input to an rvalue reference.

template <typename T>

std::remove_reference_t<T>&& move(T&& t) noexcept

{

return static_cast<std::remove_reference_t<T>&&>(t);

}

Move constructor and Move assignment

For move semantics to be functional, classes from C++11 onwards have two extra functions; move constructor and move assignment operator; making it six special functions in total. They are

- Default constructor

- Copy Constructor

- Copy assignment operator

- Move constructor -> C++11 onwards

- Move assignment operator -> C++11 onwards

- Destructor

The canonical syntax for these special functions is as below

class Window

{

private:

std::string title{};

int height {0};

int width {0};

std::unique_ptr<int> buffer{};

public:

//Move constructor

//Since all member types can be moved automatically

// we don't even need to declare below defaulted functions.

Window (Window&& w) = default;

Window& operator= (Window&& w) = default;

}

Notice that in the class definition above we don’t need to implement move functions. It’s because all the data members types are automatically movable; int is fundamental type, std::unique_ptr and std::string have their move functions implemented and thus know how to transfer content efficiently.

This may not be the case always. How about when we use int* instead of std::unique_ptr? With that, let’s see how we can implement the move functions for our classes.

How to make a class movable?

Consider a class that manually manages resources; e.g. memory, database connection or file, etc.

class Window

{

private:

std::string title{};

int height {0};

int width {0};

int* buffer {nullptr};

}

Here we can not rely on the default move functions and thus have to implement them ourselves for move to work correctly. It’s always a good idea to follow the guidelines to have a correct implementation.

Move Constructor

A well-implemented move constructor should

- Transfer the content of source object

wintothis. - Leave the source object

win a valid but defined object.

//continuing from Window class above

public:

//Move constructor

Window(Window&& w) noexcept

//Step 1: Transferring content

: height(std::move(w.height)), //No added benefit except uniform convention

width(std::move(w.width)),

title(std::move(w.title)), //Need to explicitly move string.

buffer(std::move(w.buffer))

{

//Step 2: Leaving the source object in a valid state.

//For an owning pointer, this is absolutely necessary.

// Without this, we'll have two places buffer memory can be

// destroyed from. Trouble!

w.buffer = nullptr;

//purely optional. CPP core guideline #64

w.width = 0;

w.height = 0;

w.title = {};

}

we can also use std::exchange() to make the above implementation a little more compact. Here we can combine statements to move w’s buffer to this followed by resetting it to nullptr in a single statement.

Window(Window&& w) noexcept

: height(std::move(w.height)),

width(std::move(w.width)),

title(std::move(w.title)),

buffer(std::exchange(w.buffer), nullptr) // moves the pointer and resets w to nullptr

{

//purely optional. CPP core guideline #64

w.width = 0;

w.height = 0;

w.title = {};

}

Move Assignment Operator

Similarly, a well-implemented move assignment operator should

- Clean up all visible resources.

- Transfer the contents of the source object

wintothis. - Leave the source object

win a valid but undefined state.

//continuing from above

public:

//Move assignment operator

Window& operator= (Window&& w) noexcept

{

//Step 1: Clean up all visible resources.

//We need to release old memory.

delete buffer;

//Step 2: Transferring content

height = std::move(w.height); // No added benifit except uniform convention

width = std::move(w.width);

title = std::move(w.title); // Need to explicitly move string.

buffer = std::move(w.buffer);

//Step 3: leaving the source object in a valid state.

//Without this, we'll have two places buffer memory can be destroyed from. Trouble.

w.buffer = nullptr;

//purely optional. CPP core guideline #64

w.width = 0;

w.height = 0;

w.title = {};

return *this;

}

Similar to copy constructor we can use std::swap() to make the above implementation a bit more compact. Here we swap the resources between source object w and this.

Window& operator= (Window&& w) noexcept

{

//move ints and string as before

height = std::move(w.height);

width = std::move(w.width);

title = std::move(w.title);

//swap resources

std::swap(buffer, w.buffer);

//purely optional. CPP core guideline #64

w.width = 0;

w.height = 0;

w.title = {};

return *this;

}

Although this version is more expressive, the previous version is more deterministic in terms of when the memory held by this pointer gets released, due to the explicit delete on it. In this version, we exchange the ownership of memory between w and this and we’re not sure when w gets destroyed and the old resources will be freed.

Note: It’s a better practice and often desirable to create classes where its members can be moved automatically using default move functions compiler generates. This is an extension of a similar approach about having classes which can work correctly with default copy functions.

So, when does the compiler generate default implementations of these functions?

- The default move operations are generated if no copy operation or destructor is user-defined.

- Default copy operations are generated if no move operation is user-defined.

Note: =default and =delete is treated as use-defined.

Design changes

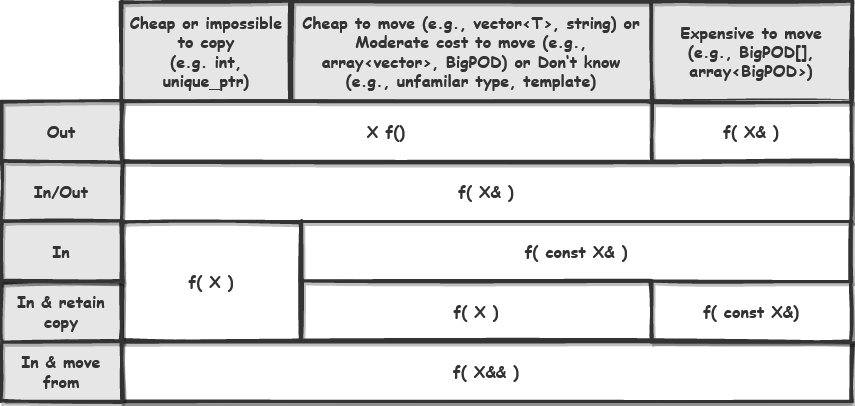

Now that we’re comfortable about the technical details of move semantics, we can look into design impacts it can have. It mainly concerns how we pass information to and from functions. Let’s look at them one by one.

Returning from functions

Before C++11, to return a large vector efficiently from a function we would follow either.

Return by pointer

std::vector<int>* GetVector(int len)

{

std::vector<int>* myVec = new std::vector<int>(len);

for(int i=0; i<len; ++i)

{

(*myVec)[i] = i+1;

}

return myVec;

}

...

...

std::vector<int>* vec = GetVector();

delete vec;

This approach puts the responsibility of memory management on the caller. OR.

Pass out-param as reference

void GetVector(std::vector<int>& myVec)

{

int len = myVec.size();

for(int i=0; i<len; ++i)

{

myVec[i] = i+1;

}

}

...

...

std::vector<int> vec;

GetVector(vec);

In this approach, we modify the parameter which is passed as a non-const reference.

In C++11, we can simply return the vector by value. This more clean and elegant.

std::vector<int> GetVector(int len)

{

std::vector<int> myVec(len);

for(int i = 0; i < len; ++i)

{

myVec[i] = i+1;

}

return myVec;

}

By now, it should be easy to guess that it works because the STL container classes have been updated to support move semantics.

Passing parameters to function

Again, with move semantics, we can avoid the extra copy of the object when passing temporaries.

std::vector<std::string> msg;

msg.push_back(std::string("Hello World")); //string is a rvalue

These changes don’t imply that one should start scrutinizing the legacy code all over and change function signatures and calling statements. Below is a cheat sheet that one can follow while designing their APIs and decide upon the changes needed.

I hope this post provided a basic understanding of move semantics and lvalue and rvalue. In summary, we learned that.

- Before C++11, containers employed value semantics, which caused unnecessary and expensive copy operation.

- C++11 introduces move semantics and rvalue references to distinguish between lvalues and rvalues.

- lvalues are named identifiers having an accessible address.

- rvalues are temporary objects and their address can’t be accessed.

- Move constructor and move assignment operator canonical definition and guidelines for custom definition.

- Conventions to pass parameters to and from functions are simplified.